A city electric bus fleet on an opex (operating expense) model means that the city or the transit agency does not purchase the buses outright, but instead, they lease or rent them from a third-party provider. The provider is responsible for owning, operating, and maintaining the electric buses, while the city or transit agency pays a fee for their use.

This model has several advantages over traditional bus procurement methods. First, it allows cities and transit agencies to introduce electric buses into their fleets without incurring the high upfront costs associated with purchasing the buses outright. Second, it can help reduce the risk of technological obsolescence since the third-party provider is responsible for upgrading the buses as technology advances. Third, it can help reduce maintenance costs since the provider is responsible for maintaining the buses.

One example of a company that provides electric bus fleets on an opex model is Proterra. Proterra offers a turnkey solution for electric bus fleets, including the buses themselves, charging infrastructure, and maintenance services. The company works with cities and transit agencies across North America to help them introduce electric buses into their fleets and reduce their carbon footprint.

The Increasing Demand for Electric Buses

The Indian electric bus industry will be ten times larger than it is now in the next five years thanks to the rapid expansion of private sector adoption and the significant rise in demand from central and state governments for electric buses. With government incentives and policy support, expanded charging infrastructure, and advancements in battery technology, India can significantly expand the use of electric buses to meet the needs of expanding urban centers.

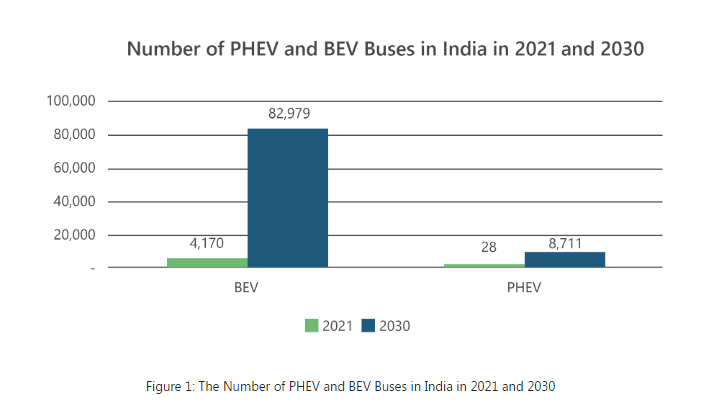

Battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) are two types of electric vehicles. There are no gas engine parts in Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), which are only powered by an electric battery. The majority of BEVs can be quickly charged. Lithium-Ion Phosphate (LFP), Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC), and Lithium Titanium Oxide (LTO) are the three types of EV batteries that are utilized the most frequently. In terms of battery technology, lithium-ion batteries are currently the sole option for all OEMs. However, it has been reported that OEMs use a variety of battery chemistries; For instance, Olectra-BYD provides lithium-ion phosphate batteries (LFP), while Tata Motors uses lithium-NMC (lithium nickel manganese cobalt). To charge their e-buses, almost all OEMs use plug-in battery charging technology, also known as normal conductive charging. Even though everyone claims that there are both fast and slow charging options that are flexible, the slow charging option is preferred. However, Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) combine a small to medium-sized combustion engine with an electric powertrain to enable full electric operation, conventional fuel use, or a combination of the two.

According to the PTR database, there will be a rise in the number of electric buses in India between 2021 and 2030, with BEV buses outnumbering PHEV buses, as shown in Figure 1.

The second phase of the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles (FAME) program was officially launched in March 2019 by the Indian government. In addition, the government announced plans in August 2019 to acquire 5,585 electric buses to aid in environmental cleanup.

The Department of Heavy Industry (DHI) received an overwhelming response to the Expression of Interest (EOI) from 26 states and Union territories, with a total of 86 proposals for the deployment of 14,588 e-buses. The government has approved 5,595 e-buses for 64 cities, including 5,095 e-buses for intra-city bus operations, 400 e-buses for intercity bus operations, and 100 e-buses for the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation ( According to DHI’s estimate, these buses will run for 4 billion kilometers without emitting any emissions from their exhaust pipes. It is anticipated that this will prevent the importation of approximately 1.2 billion liters of oil and 2.6 million tCO2 emissions.

Since just 4,500 of the 7,000 transports have been offered up until this point, something like 2,500 additional vehicles should be bought. Even if nine cities split the remaining buses, each city will eventually have at least 500 e-buses. On their way to Delhi and Bengaluru are 500–600 electric buses, or about 10% of the entire e-bus fleet.

State-Level Incentives Driving E-Bus Adoption

The following is a list of state-level interventions primarily aimed at increasing the use of electric buses in India.

By 2024 and 2029, Andhra Pradesh intends to have 100% of its bus fleet run on electric power in major cities and across the state.

By 2022, Delhi has committed to converting 50% of all stage carriage buses.

By 2025, Kerala intends to replace their entire bus fleet with more than 6,000 new buses.

The state of Tamil Nadu has decided to purchase 1,000 e-buses annually.

By 2028 and 2030, respectively, the draft EV policies of Madhya Pradesh and Telangana aim to convert their bus fleets completely.

The permit fee and MV tax have been waived for private e-bus operators by the Punjab Government.

E-buses are now exempt from Assam’s state GST.

The OPEX model will be used to acquire 80 electric buses for the state government of West Bengal. In the OPEX model, the vendor chosen through competitive bidding bears the costs of acquiring, ticketing, and operating the vehicle, while the government pays per kilometer charges.

Looking Ahead

In Indian cities, the majority of commuters use public transportation, particularly buses; Consequently, the e-mobility program that focuses on public transportation is extremely relevant to India’s goal of decarbonization. One chance to reduce risk and decarbonize a significant portion of daily travel is through electric buses.

Although it is understandable that electric vehicle incentive programs give buses priority, the incentive’s design still needs to be significantly improved to ensure its successful implementation. To streamline ridership and outflows gains, future changes should lay out another biological system for e-transports that has suggestions for procedures of obtainment, arrangement, administration conditions, charging options, skilling, and the observing of administration levels.

As India’s bus market expands at a faster rate, state-level electric vehicle policies should include more specific targets and support for e-buses. In addition, a variety of regulations must be complied with in order to address OEM concerns like range anxiety, the selection of the appropriate charging technology in light of the limited options, fleet planning and the preparation of e-bus schedules, performance monitoring of buses, capacity enhancement of existing staff, and other similar issues.

Public private partnership in operation and maintenance of electric buses in cities (OPEX Model)

The Government of India’s National Institute of Transforming India (NITI) Aayog has taken the initiative to provide a Model Concession Agreement (MCA) document for the introduction of an Electric-Bus Fleet for Public Transportation in Cities via PPP on an Operational Expenditure (per km basis) Model. The said model record has been created in light of global prescribed procedures, and with perspective on giving cleaner, more productive and reasonable public transportation. The objective is to guarantee the project’s bankability for the private sector while simultaneously improving the authority’s O&M efficiency for the city bus fleet. The authority will be responsible for operating costs per kilometer, while the concessionaire will be responsible for the necessary capex for acquiring the e-buses and O&M infrastructure.