Building E-Mobility Ecosystem

We help you make, your career transition to EV Industry.

Get your hardware enabled training at our Global Hybrid E-Mobility Centers.

What's New

Press Releases - Media

-

-

-

-

“Women in E-Mobility” Scholarship by DIYguru.

Press Release March 17, 2023

Free Live Webinars

-

-

(Finite Element Method) FEM Workshop

Webinar November 7, 2022 -

Modeling of Electric Vehicle using MATLAB/Simulink

Webinar March 27, 2022 -

Popular Programmes

Courses

DIYguru Learning & Development is recognized

as a leader in training for Mobility

engineers.

Explore Courses

Recruitments

DIYguru offers a wide variety of mobility engineers

with range of working experience

from freshers to experienced.

DIYguru Mentors Help Create the Journey

Featuring talks from industry veterans

Arindham Lahiri

CEO - ASDCAnil Chhikara

CEO - Bluebolt ElectricBuddha Chandrashekhar

CCO - NEAT AICTERamesha BS

AltairChinmaya Chetan Biswal

BeepkartKarthik A

Co-Founder Urban SphereBhanu Pratap Singh

CEO - doReal MotorsAbhishek Dwivedi

Co-Founder EVeezDr Sugumaran Permul

CEO – JV Skill, MalaysiaDr Vijay Chauthaiwale

Ph.D. In-Charge, Foreign Affairs Dept MemberArvind Gupta

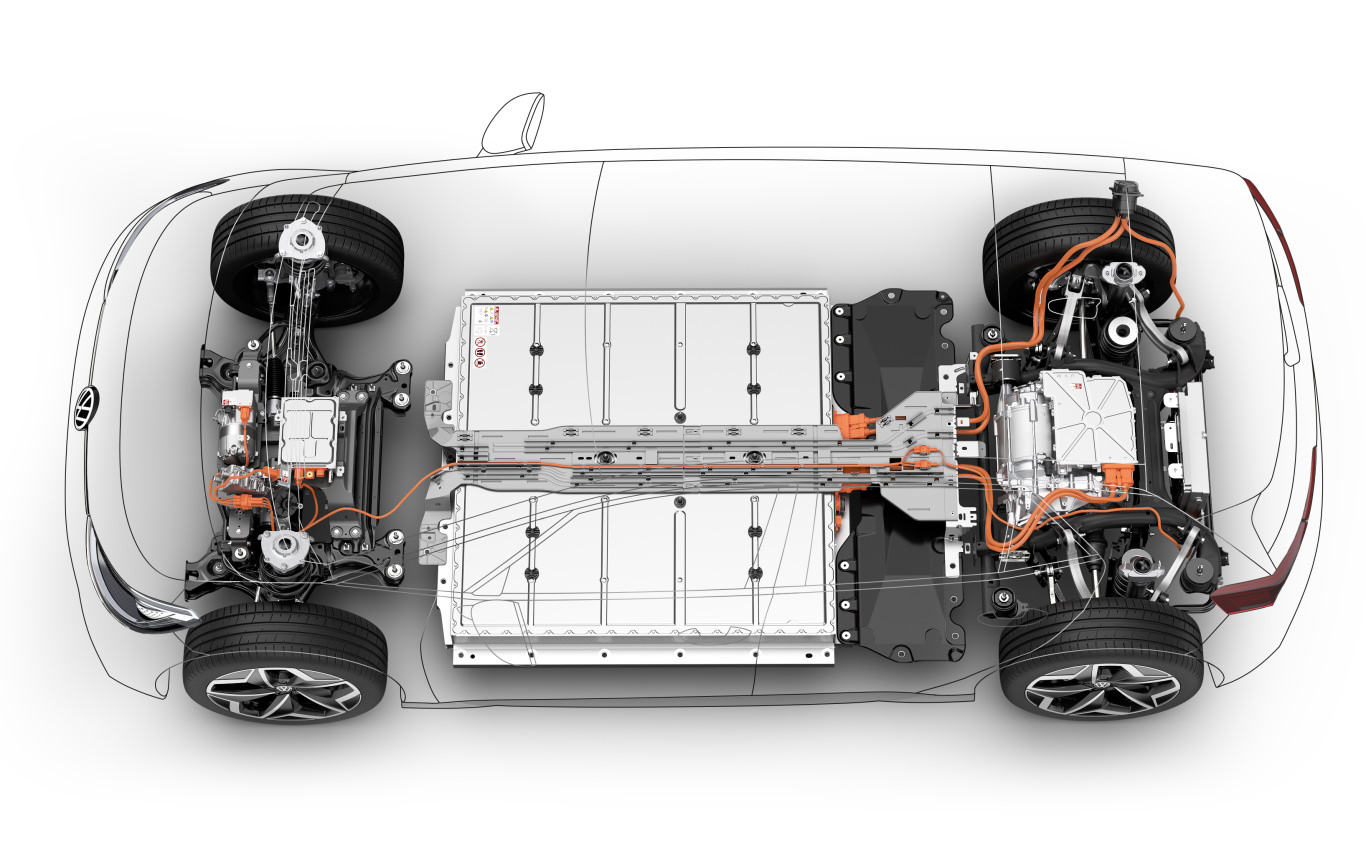

Co-Founder Digital India FoundationUnderstand the Future Mobility

Aquire deep knowledge in Mobility System architecture with thorough understanding of component design and development in automotive industry.

Learners love DIYguru

Here’s what some of our 40,000+ satisfied learners have to say about studying with DIYguru Team.

"Very informative course, high quality in terms of quizzes and assignments, liked the project at the end of the course. Oh, and great support. Can recommend this one to my friends and colleaugues. Being the very first player in EV industry, DIYguru has been crucial to the EV ecosystem development in india"

"I have known DIYguru since 2013 when the first version Autosports india was launched and in last 6-8 years the platform has emerged as the leading maker's learning platform in india. Form me the team behind DIYguru has been the best support all through the journey after Bachelors till my master's"

"Some of the best customer service I've ever seen. Great platform for mechanical and electrical engineers to learn EV!"

"This is truly a 5 star experience for youngsters in india! keen to learn about EV Technology"

"The platform has helped me personally to build my career in renewable energy in Canada. Hope to see DIYguru in Canada soon. Five stars!"

"liked the course with wide range of calculations in EV, all tutors are very supportive."

"Automotive design with incredible knowledgebase in terms of support from Baja Tutor community of DIYguru is wonderful experience. Documentation on the web is also good. "

"Amazing content and great support from DIYguru community"

Recent Placements @DIYguru

Avg. Salary Package > 3.5L

66% Alumni Career Transitions

50% Average Salary Hike

73+ Hiring Partners

Over 1.2 Million+ learners impacted worldwide

Learners from 170+ countries have grown in their career through our programs

Get in touch to learn more about how you can make the best of your talent

Spend less time worrying about job availability, and more time growing your knowledge. Join DIYguru Program today.

If you’re a current student, please get in touch through the DIYguru dashboard to ask about more details of this Program.

Please note, eligibility for this course is reserved to students who have done related projects and have relevant profiles matching with the pre-requisite of this course.

The DIYguru team hold the right to cancel your admisssion into the program without any explanation via email if found unsuitable and unfit.

Our 7-day money-back guarantee starts from the moment of signup and runs through the free week. Cancellations between days 7 and 30 will get a prorated refund.

Fees for the program is charged only when the admission is approved.